|

Volunteers sampling benthic invertebrates living in McAleer Creek.

Photo by Dan Benson |

By Brian Saunders, LFP Stewardship Foundation Board Member

The biological health of Lyon and McAleer Creeks has been sampled in Lake Forest Park (“

LFP Streamkeepers team-up with LFP Stewardship Foundation to sample local streams” 10/25/21 SAN) for many years. A tale of how different these two creeks might be has emerged, even though they flow within 200 feet of each other as they make their way through Lake Forest Park to north Lake Washington.

As an instructor at Shoreline and North Seattle College, I am fortunate to have access to good equipment, such as a dissecting microscope, ideal for observing insects and their delicate anatomical structures. I am looking at a member of the Ephemeroptera (E·PHEM·er·op·ter·a), an insect order of mayflies, highly coveted by fly fishing aficionados. Having trained as a marine biologist, studying creatures like soft-bodied anemones, my recent interest in identifying freshwater invertebrates has brought me a sense of nostalgia. Counting the number of thoracic (body) segments, the positioning of abdominal gills, and looking up unfamiliar terms such as “cerci”, recalls long afternoons in a cold laboratory at Shannon Point Marine Station in Anacortes where I received my Masters at Western Washington University in the mid 1990’s.

Why do we care what (and how many) invertebrates live in a stream?Identifying aquatic insects of streams provides a good deal of information regarding stream health. In the October article, I described how some aquatic “bugs” are very tolerant to pollution and human disturbance while others are not. By collecting, identifying and counting these organisms, scientists have developed quantitative formulas that score each waterway, to determine which are in excellent condition and which are fair to very poor (

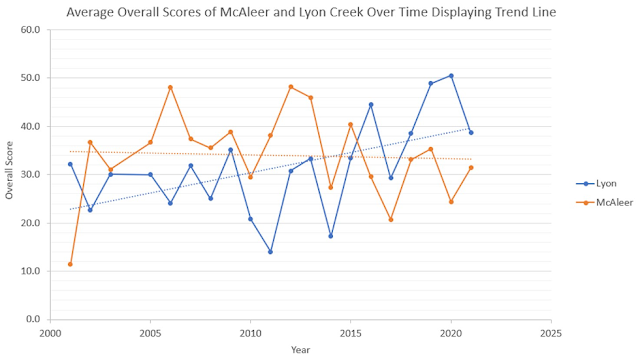

https://pugetsoundstreambenthos.org/). Examining 20 years’ worth of data on the biological health of Lyon and McAleer Creek, has revealed two creeks on two different health paths. Further examination of the chemical health of the creeks over the past 50 years, suggests that their future ability to support the present-day biota looks dour, unless strong actions to protect and mitigate human disturbances are taken.

|

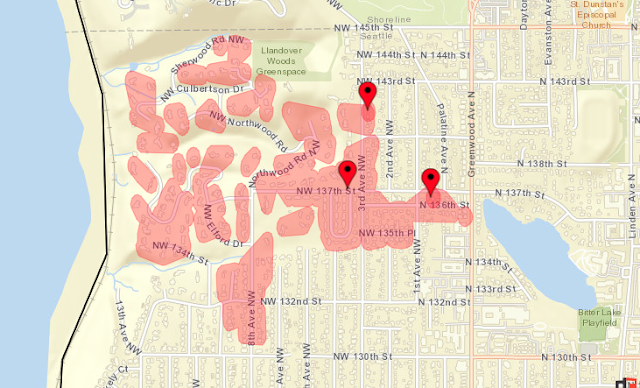

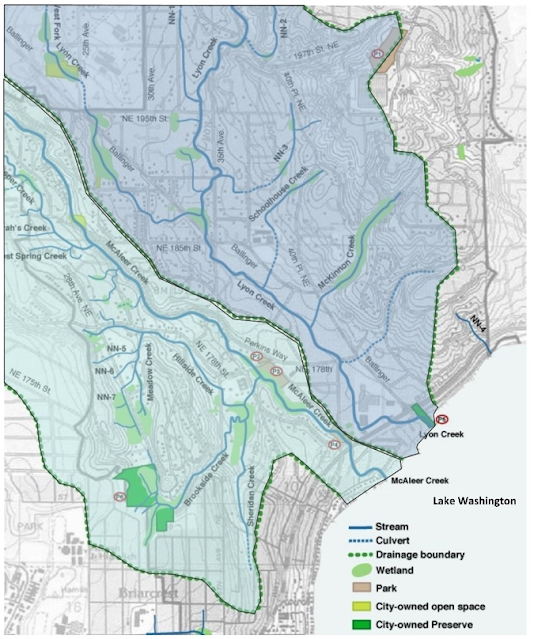

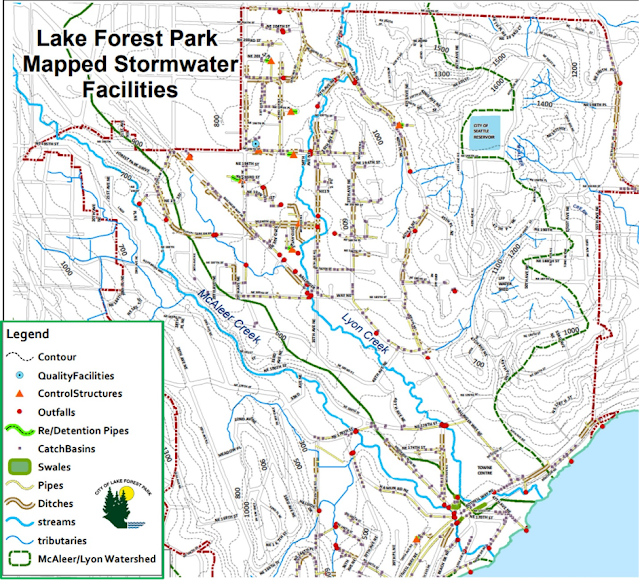

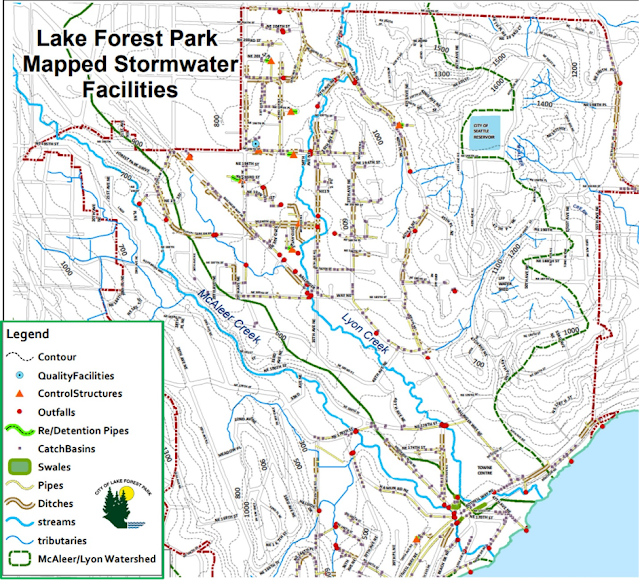

| Drainage areas for McAleer (green shaded) and Lyon Creeks (blue shaded) in Lake Forest Park. |

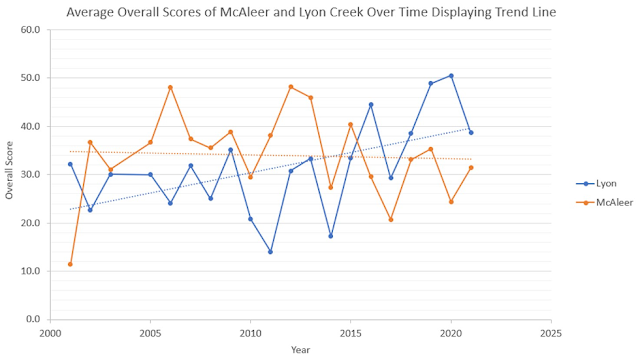

A Look at the Overall Health ScoresThe first thing to know is that both Lyon and McAleer Creeks are in Fair to Poor condition regarding their biological health, with McAleer slightly, but significantly, healthier than Lyon. A closer look at the specific organisms found in each creek showed that McAleer had significantly greater diversity of Stoneflies (a taxonomic group under the Order Plecoptera, known to diversify in healthy streams), and Clinger species (organisms that cling to surfaces between rocks and cobble along the bottom of the stream and are susceptible to being smothered by pollution and sediment). McAleer also had significantly less Tolerant species (species that are better adapted to polluted or disturbed creeks).

A Look at the Health Over TimeAn environmentally conscious citizen isn’t just content to know the overall health of a neighborhood creek. They would also be interested in determining how it has fared over time and what might it look like in the future. With 20 years’ worth of data, we are fortunate enough to be able to do so, even though the data used to analyze the health of McAleer, and Lyon Creek was not collected by a single group, nor has it been conducted at the same site along the creek, or on the same dates from year to year. All of which can produce variability in analyzing the data and thus, can affect the interpretation of results and skew conclusions. We should all recognize that this preliminary account and should enthusiastically spur more data collection to fine-tune a clearer picture.

McAleer and Lyon Creek appear to be heading in opposite directions with their overall health trends. Over the past 20 years, McAleer Creek has been slowly decreasing its overall score. Specifically, the diversity of Predators in the creek has decreased and there has been an increase in Dominant species (less healthy creeks tend to be dominated by fewer, larger groups).

|

| Overall Scores for Lyon and McAleer Creek over time. |

In contrast, Lyon Creek has been increasing significantly in its overall health score over the last 20 years. Specifically, the number of Stoneflies, Caddisflies, and Long-lived species have been slowly increasing. Does this mean the Lyon Creek will soon be in good to excellent health while McAleer is doomed to an unhealthy future? Doubtful on both accounts. We can’t possibly predict future health of these two creeks without determining the factors that are affecting each creek and how or if they can be mitigated.

Of Roads and Recent HistoryIt would take me several more articles to fully cover all the variables that affect McAleer and Lyon Creek and their biological health. For example, the area of developed versus undeveloped land the creek flows through, the total drainage area that each creek covers, proximity to non-point and point source pollutants, and the creek volume and flow rate. After researching a few of these variables, a few things popped out in the data: Roads and Creek History.

|

Typical storm drain in LFP that often

transports water directly into streams. |

Stream ecologists have long known about the negative effects roads have on waterways. Roads are impervious surfaces that collect dirt, oil, and chemicals that would normally be filtered out before entering a stream if they were allowed to drain through a pervious ground. Storm drains that collect this toxic runoff, often drain directly into creeks. One of these chemicals, newly discovered from tire wears, is known to be the leading cause of pre-spawn mortality in Coho salmon (see article here:

Sure enough, when I looked at the biological data in respect to testing sites distance from the nearest road, that there was a significant “road” effect in the overall health score. Specifically, the overall score and species richness increased the further away from the road. Data like this should help us understand the significance of buffer zones for development projects near or along water systems.

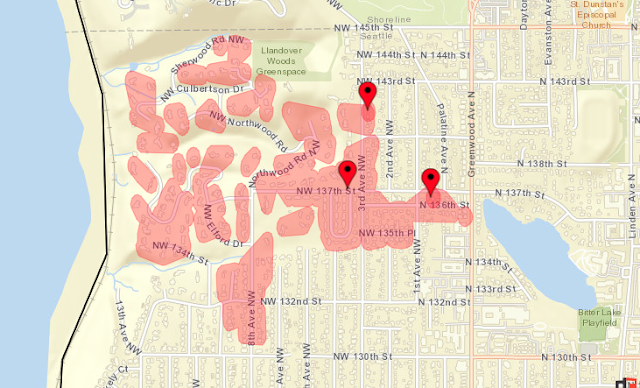

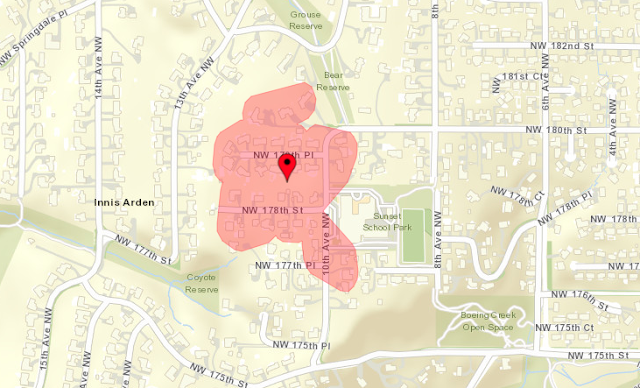

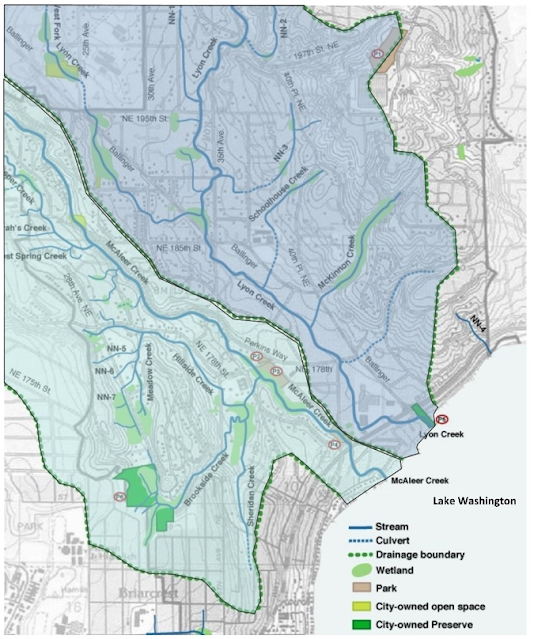

Roads can affect creek health in other ways, even if the nearness to a creek is not directly obvious. When I analyzed the data from the different sites located in the upper regions of Lyon in comparison to the lower regions, I found the upper regions were significantly less healthy. Starting close to the headwaters of Lyon Creek in Mountlake Terrace just north of Terrace Creek Park, the overall health score of Lyon creek increased traveling downstream. A quick look at a city map showing the location of outfalls, pipes, control structures and ditches, all of which can severely disrupt the biological ecosystem of a creek, might help us understand why the upper regions of Lyon creek is relatively poor health compared to its lower region.

|

City map of Lake Forest Park identifying structures that may impede or

adversely affect Lyon and McAleer Creek |

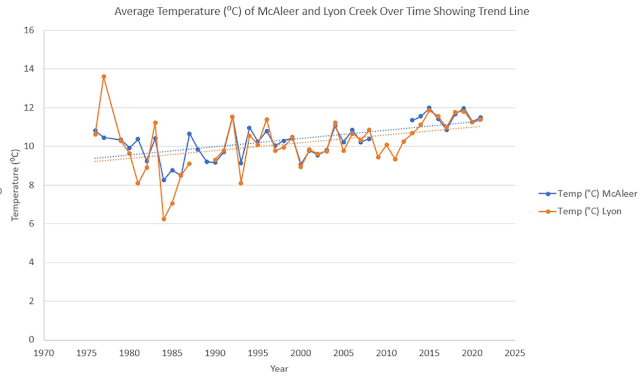

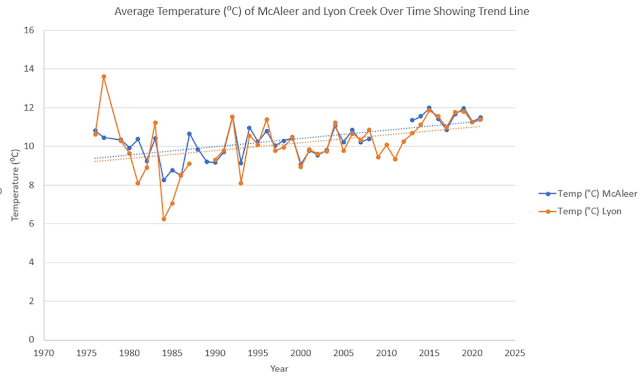

Climate Change and the Future of Lyon and McAleer CreekClimate change awareness is growing. Humans have increased the average temperature of the planet by almost 1.5 ⁰C since the dawn of the Industrial Age, some 200 years ago. Surface currents are changing, and deeper waters are becoming more acidic. Extreme weather conditions are intensifying. Animals and plants are migrating into new latitudes and others are being displaced as their habitats change. By examining the chemical parameters of Lyon and McAleer Creek, I have found evidence that they are not immune to these forces of change.

The Department of Ecology began collecting data on Lyon and McAleer Creek in 1976 and although testing hasn’t always been consistent, trends over time are starting to emerge

|

| Regression analysis of temperature change for Lyon and McAleer Creek over time. |

Both Lyon and McAleer Creek are significantly increasing temperature by +0.05 ⁰C per year. The average annual temperature of Lyon and McAleer creek has increased by +1.2 ⁰C since 1979. This could be due to the warming climate but also from increased development that reduce tree /riparian cover, preventing valuable shade to cool the water. This paints a gloomy picture for the present-day biota living in the creeks. The Washington Department of Ecology has assessed that 13 ⁰C is the Upper Threshold (non-summer) of tolerance for the more sensitive species at which point, will no longer survive. Extrapolating from the data trend, Lyon Creek will have an annual average of 13 ⁰C by 2038. Does this mean our creeks are doomed to be lifeless? No, they just won’t be able to support the life we see today or have seen in the past. They certainly, won’t support the iconic salmon species we know.

We Must Still Have Hope, and Take ActionThinking back to the gray, overcast day in October when neighbors gathered to organize and strategize a day of biological sampling, I remember how invigorated and spirited people were. It was a day of hope. We are still hopeful. We understand that much harm has been done to both Lyon and McAleer Creek, some may be irreversible, but we still have hope. The hope that we cling to is embodied by a single species we collected on that day that, which has not been seen in either creek over the past 20 years. Cinygmula!

|

A picture of a species in the genus Cinygmula

which are sensitive to aquatic pollution. |

A flat-headed species of Mayfly; the same group I introduced to you at the beginning of this article. This genus of Ephemeroptera appears more alien-like than emblematic, but a species of great importance and hope. Cinygmula is not any ordinary stream aquatic macroinvertebrate but is very intolerant to pollutants and human disturbance. The delicate feathery abdominal gills and lengthy three-tails speak to me of resilience and possibility. By enforcing buffer zone restrictions around creeks, mitigating road-runoff directly into creeks, and restoring areas that have been adversely impacted, it may be possible to entice more cinygmula-like species to return. And with their return, so does hope.

Streamkeepers and the LFP Stewardship Foundation is a cooperative volunteer group of local citizens who have a deep passion for the health and protection of McAleer and Lyon Creek.

Read more...